By MALUM NALU

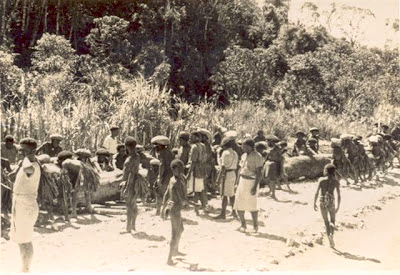

How kiaps got things done in the colonial days

Back in 2010, I used to frequent the Weigh Inn Hotel at Konedobu, Port Moresby, to have a pint and a quiet yarn with former kiap (patrol officer) and Member of the First House of Assembly Graham Pople.

At that time, the much talked-about 2010 census had been deferred to 2011 because of various reasons, including “insufficient funding”.

Eventually, the census was never held, and a population estimate was made.

To this day, in 2022, the exact population figure of PNG is not known.

Pople, who later became a citizen of Papua New Guinea, died in February 2019 aged 83.

Pople’s never-before-published autobiography and patrol diaries contain reminisces of his days as a kiap and Member of the first Papua and New Guinea House of Assembly in 1964.

Simply titled The Popleography, it gives a fascinating insight into life in the then Territory of Papua and New Guinea in pre-independence days, as well as the First House of Assembly.

Pople writes candidly about how he conducted a census and maintained law-and-order in Laiagam, Enga, in (then part of Western Highlands) in 1959.

Indeed food for thought as I wondered what had gone wrong and why National Statistical Office staff had conducted the cardinal sin of not conducting a census in its scheduled year: something that had never been done before.

“Most of my time while at Laiagam was spent in patrolling,” Pople remembers.

“My initial job was to go around the valley recording names in village, clan and lineage groups.

“(I) Recorded some 65,000 names in the Lagaip Valley.

“Every day was also a court day.

“Court day often meant just that, but often it was more of a mediation process.

“If a dispute could be settled amicably by paying pigs or shell than that was the chosen way to do it.

“Prison terms were often given that but that was mainly for assaults or garden theft or rioting and fighting.

“There was no paid labour on the government station and all upkeep was done by the prisoners.

“They had no complaints.

“They were houses and fed and generally happy for their period in gaol.

“They knew they had done something wrong and accepted it.

“The only escapes were when someone heard that his wife was playing up or a child was sick or his pig had been killed.

“But application to the POIC (patrol officer in charge) was often given a sympathetic hearing and he was allowed out in the custody of his village leader or luluai.

“The capacity of the prison was space limited to about 30 occupants.

“On one occasion, there was a tribal fight in which two major clans were involved and some 400 warriors were sentenced by me to a gaol term.

“It was impossible for me to accommodate them, so after discussions with the two luluais involved it was agreed that each clan would work on the section of the road through their tribal areas for the term of their gaol sentence.

“They would sleep in their own houses and their wives/mothers would bring food to where they were working.

“A daily roll call, to ensure attendance, would be held.

“It worked very well and everybody benefitted with the road work that was completed during the two-month period.

“They knew that they had done wrong and accepted the punishment, but were happy to have the trust-like system which allowed them to sleep in their warm houses as opposed to the prison where their only warmth would come from a blanket or two.

“In 1969, 10 years later when I returned to the area, several of them pointed out with pride the work they had done on the road.

“This was no resentment.”

Pople first arrived in Mt Hagen, Western Highlands, in 1959 and served places such as Jimi, Tambul, Tomba, Wabag, Laiagam, Porgera, Mt Kare, Koroba (Southern Highlands), Kandep, Minj and Banz.

“At this time,” he recalls, “Mt Hagen was growing rapidly but shopping was rudimentary to say the least.

“Danny Leahy had a small store not far from where we lived and there were a couple of other small stores on our side of town.

“On the other side, where the people lived, there were better stores, and if memory serves me well, they were New Guinea Company, Steamships and Burns Philp.

“Hagen was a centre for coffee-growing which was growing rapidly at that time in the Highlands.

“In later years, that spread to tea-growing but that had not yet started when I first arrived there.”

Tambul, at 7,300ft and the highest station in the Territory of New Guinea at that stage, had an airstrip that was capable of taking DC3 and similar larger aircraft.

Wabag airstrip was at 6,700ft above sea level and built on a sloping ridge with an approach up the valley, a lift on to the end of the airstrip and then full-throttle to climb to the parking bay.

Whilst Pople was at Laiagam, there was always talk of gold at Progera, but he had resolved to stay out of anything to do with Porgera gold and, though offered gold on many occasions, never bought any.

In 1960, Pople was posted to Minj, “which had only been opened in 1957, when Barry Griffin had been sent to pacify the warring locals and open a station”.

“They were an offshoot of the middle Wahgi people and had close affiliations with the people from North Wahgi area.

“There were about 25,000 of them living in the headwaters of the middle Jimi and about another 500 scattered through a large area in the lower Jimi.

“Mt Wilhelm was part of the watershed of the Jimi and the valley dropped down to about 4,500ft near the station to under 1,000ft in the sparsely-populated lower Jimi.

“They were still fighting and there were two mission stations operating.

“One was the Catholic Mission at the foot of Mt Wilhelm at the head of the Jimi River and the other was operated by the Anglican Mission on the north side of the Jimi River.”

Minj and Banz in the great Wahgi Valley were also two other places which Pople resided in and remain close to his heart after almost a half-century.

I’ll leave the last word about him camping one time at Karepuga in Mt Kare in 1959, which some 29 years later, in 1988, would be the scene of PNG’s biggest-ever gold rush.

“We camped in grassland but at the edge of light bush at an altitude of 9,500ft.

“The bush provided some relief from the winds and we all had a better sleep.

“This camp was just to the north of Pinuni creek and only a kilometre away from the area which was to provide the source of the biggest gold rush in PNG history some 29 years later.

“I was obviously not born lucky!”